Do your spirits need a lift? In this time of raging COVID-19 and President Trump’s outrageous behavior towards President-elect Biden, my heart has been gladdened by picture books casting new light upon Hanukkah. One of these charming works is particularly well-suited for young readers whose families may celebrate Christmas as well as this upcoming Jewish holiday. All these books emphasize human determination, generosity, and emotional connections, regardless of religious affiliation—or lack of any affiliation. Their refreshing takes on Hanukkah, each deploying a child-friendly literary tradition in a new way, are comfortingly familiar even as they are engagingly different.

Do your spirits need a lift? In this time of raging COVID-19 and President Trump’s outrageous behavior towards President-elect Biden, my heart has been gladdened by picture books casting new light upon Hanukkah. One of these charming works is particularly well-suited for young readers whose families may celebrate Christmas as well as this upcoming Jewish holiday. All these books emphasize human determination, generosity, and emotional connections, regardless of religious affiliation—or lack of any affiliation. Their refreshing takes on Hanukkah, each deploying a child-friendly literary tradition in a new way, are comfortingly familiar even as they are engagingly different.

The Hanukkah Magic of Nate Gadol (2020), written by literary luminary Arthur A. Levine and illustrated by the accomplished Kevin Hawkes, creates a new mythic character to represent Hanukkah, much as Santa Claus is a secular representative of Christmas. In fact, in this picture book we discover that Nate Gadol and Santa are old friends! This title character’s name comes directly from the supposed miracle that occurred at the end of an ancient fight for religious freedom, commemorated during Hanukkah. When only one day’s holy oil was left in the main Jewish temple, it miraculously lasted eight nights. World-wide, Jews now recognize the Hebrew words “Nes gadol haya shem”, meaning a “A great miracle happened there,” attached to the dreidel (spinning top) game typically played each Hanukkah night. Nate Gadol echoes “nes gadol.”

The Hanukkah Magic of Nate Gadol (2020), written by literary luminary Arthur A. Levine and illustrated by the accomplished Kevin Hawkes, creates a new mythic character to represent Hanukkah, much as Santa Claus is a secular representative of Christmas. In fact, in this picture book we discover that Nate Gadol and Santa are old friends! This title character’s name comes directly from the supposed miracle that occurred at the end of an ancient fight for religious freedom, commemorated during Hanukkah. When only one day’s holy oil was left in the main Jewish temple, it miraculously lasted eight nights. World-wide, Jews now recognize the Hebrew words “Nes gadol haya shem”, meaning a “A great miracle happened there,” attached to the dreidel (spinning top) game typically played each Hanukkah night. Nate Gadol echoes “nes gadol.”

In this book, Nate Gadol is a magical character credited not only with the holiday’s original supposed miracle but also with dispensing gifts to good needy Jewish people. Levine’s main story shows how the children of one 19th century immigrant family, the Jewish Glasers, receive winter holiday presents just like their Christmas-celebrating neighbors. In his final “Author’s Note,” Levine, who is Jewish, does not view the children’s wish for presents as a “December dilemma,” as many traditional Jews still do, but as just one part of Jewish-American history. It is, Levine writes, just “a bit more mythology” added to a religious holiday, similar to Santa, his elves, and reindeer. (Along the way, I also see that the supersized Nate Gadol is shown fixing some colossal problems, such as a burst dam, akin to the spectacular deeds of such American tall tale heroes as Paul Bunyan—a further link with traditional Americana.)

In this book, Nate Gadol is a magical character credited not only with the holiday’s original supposed miracle but also with dispensing gifts to good needy Jewish people. Levine’s main story shows how the children of one 19th century immigrant family, the Jewish Glasers, receive winter holiday presents just like their Christmas-celebrating neighbors. In his final “Author’s Note,” Levine, who is Jewish, does not view the children’s wish for presents as a “December dilemma,” as many traditional Jews still do, but as just one part of Jewish-American history. It is, Levine writes, just “a bit more mythology” added to a religious holiday, similar to Santa, his elves, and reindeer. (Along the way, I also see that the supersized Nate Gadol is shown fixing some colossal problems, such as a burst dam, akin to the spectacular deeds of such American tall tale heroes as Paul Bunyan—a further link with traditional Americana.)

Hawkes’ richly-colored, painterly illustrations emphasize this connection with American history, depicting Nate dressed in clothing worn during the Revolutionary War. Hawkes’ illustrations, gleaming with gold much like Nate’s eyes—”shiny as golden coins and. . . smile that was lantern bright,”—also complement the joyful receipt of gifts by Levine’s characters. The immigrant Glaser children and parents are worthy of gifts because of their generosity to their fellow immigrants, the O’Malleys. Packaged gifts are shown by the book’s end to be a new, delightful part of their American Hanukkah.

Generosity, compassion, and family feeling, however, remain more important than gifts, with the Glasers buying the O’Malleys needed medicine with money they might have spent on Hanukkah chocolate. Mrs. Glaser also is shown earlier quietly giving up her own tiny bit of chocolate to her children. Then, Nate Gadol steps in to magically reward these good deeds with those presents! This brief, warm-hearted book will be best appreciated by young readers who already have some knowledge of Hanukkah and its traditions.

Similarly, some familiarity with Hanukkah will enhance enjoyment of Little Red Ruthie: A Hanukkah Tale (2017), written by Gloria Koster and illustrated by Sue Eastland. This variation on “Little Red Riding Hood” proudly acknowledges its literary heritage in Koster’s opening dedication to her mother, “who gave [her] the gift of fairy tales once upon a time.” In an interview, the author has explained that another of her favorite fairy tales, the “Snow Queen,” inspired the icy, snow-laden setting of “Little Red Ruthie.” Her modern-day Ruthie is going to her Bubbe’s house (“Bubbe” is the Yiddish word for Grandmother) to again make potato pancakes, a traditional Hanukkah food, with her. In fact, Ruthie’s recipe for these “yummy ‘latkes’ ” (Yiddish for pancake) concludes this playful, positive book.

Similarly, some familiarity with Hanukkah will enhance enjoyment of Little Red Ruthie: A Hanukkah Tale (2017), written by Gloria Koster and illustrated by Sue Eastland. This variation on “Little Red Riding Hood” proudly acknowledges its literary heritage in Koster’s opening dedication to her mother, “who gave [her] the gift of fairy tales once upon a time.” In an interview, the author has explained that another of her favorite fairy tales, the “Snow Queen,” inspired the icy, snow-laden setting of “Little Red Ruthie.” Her modern-day Ruthie is going to her Bubbe’s house (“Bubbe” is the Yiddish word for Grandmother) to again make potato pancakes, a traditional Hanukkah food, with her. In fact, Ruthie’s recipe for these “yummy ‘latkes’ ” (Yiddish for pancake) concludes this playful, positive book.

Eastman’s full-color illustrations, created with computer graphics, aptly use red throughout the revised fairy tale. Instead of a hood, Ruthie is bundled up in a scarlet, puffy down jacket, while interior scenes in Ruthie’s and Bubbe’s houses feature red décor and clothes. Outdoors, red-tinged squirrels and birds stand out against the snowy confrontations between Ruthie and the wolf. The exaggeratedly cartoonish features of that creature are a visual reassurance that Ruthie will triumph here. Yet it is the way she tricks the wolf that is notable.

Unlike some traditional Red Riding Hoods, Ruthie does not require rescue by someone else. She reminds herself to be “brave as the Macabees,” the heroic warriors in the Hanukkah story, and she cleverly delays the wolf by playing upon his greedy appetite. Being an “excellent reader” also helps Ruthie, as reading Bubbe’s note helpfully explains where her grandmother is and when she will return. Determination, family feeling, and literacy—as well as the ability to prepare a delicious Hanukkah food, all the while explaining the holiday’s story—are the values and achievements extolled in this seemingly simple tale.

Unlike some traditional Red Riding Hoods, Ruthie does not require rescue by someone else. She reminds herself to be “brave as the Macabees,” the heroic warriors in the Hanukkah story, and she cleverly delays the wolf by playing upon his greedy appetite. Being an “excellent reader” also helps Ruthie, as reading Bubbe’s note helpfully explains where her grandmother is and when she will return. Determination, family feeling, and literacy—as well as the ability to prepare a delicious Hanukkah food, all the while explaining the holiday’s story—are the values and achievements extolled in this seemingly simple tale.

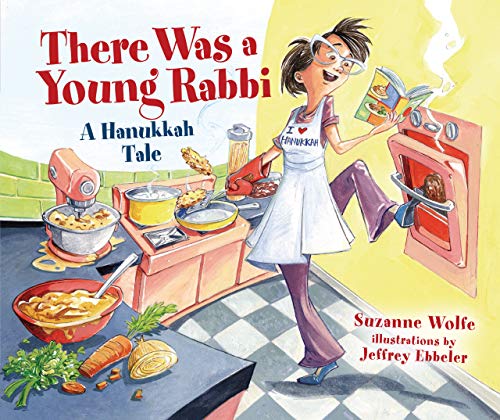

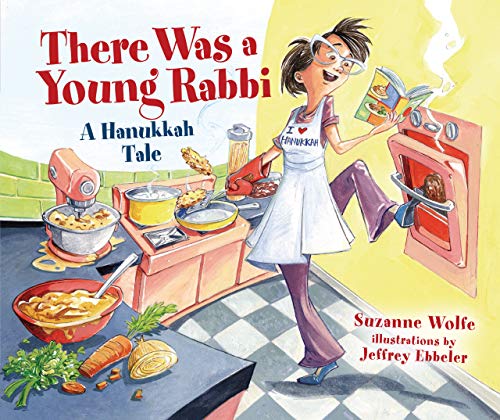

Family warmth and connectedness are also extolled in There Was a Young Rabbi: A Hanukkah Tale (2020), written by Suzanne Wolfe and illustrated by Jeffrey Ebbeler. This picture book draws upon the cumulative rhyme tradition exemplified in “There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly” and, particularly at this time of year, in the traditional English Christmas carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

Family warmth and connectedness are also extolled in There Was a Young Rabbi: A Hanukkah Tale (2020), written by Suzanne Wolfe and illustrated by Jeffrey Ebbeler. This picture book draws upon the cumulative rhyme tradition exemplified in “There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly” and, particularly at this time of year, in the traditional English Christmas carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

This picture book shows a young woman rabbi successfully juggling her synagogue obligations with preparations for Hanukkah, a religious holiday notably celebrated at home. So, watched and at times helped by her husband and elementary-aged children, the rabbi is both very busy as well as happy! On single  pages and on a few double-page spreads, we see images that add visual pleasure to such refrains as “There was a young rabbi who played dreidel to win. She watched it closely as it started to spin. /The dreidel—it spun. The rabbi—she won! Kosher brisket she made. At least ten pounds it weighed.” For young readers unfamiliar with Hanukkah, some pages have a brief boxed fact in unobtrusive type at the bottom of the page. Also, these readers will benefit from the short overview of the holiday provided on the book’s final page. (Youngsters will have to learn elsewhere that some Jewish denominations still do not accept women as rabbis.)

pages and on a few double-page spreads, we see images that add visual pleasure to such refrains as “There was a young rabbi who played dreidel to win. She watched it closely as it started to spin. /The dreidel—it spun. The rabbi—she won! Kosher brisket she made. At least ten pounds it weighed.” For young readers unfamiliar with Hanukkah, some pages have a brief boxed fact in unobtrusive type at the bottom of the page. Also, these readers will benefit from the short overview of the holiday provided on the book’s final page. (Youngsters will have to learn elsewhere that some Jewish denominations still do not accept women as rabbis.)

Every reader will smile at Ebbeler’s cheerfully colorful, cartoon-like drawings, with grandparents whose features and big eyeglasses resemble the rabbi’s coming to celebrate one holiday night. On another night, Hanukkah food and games are shared with a child guest, her wheelchair no obstacle to enjoying the menorah’s bright lights and holiday fun. Reading this story book aloud, for those who do celebrate Hanukkah, might just become a new family tradition!

Every reader will smile at Ebbeler’s cheerfully colorful, cartoon-like drawings, with grandparents whose features and big eyeglasses resemble the rabbi’s coming to celebrate one holiday night. On another night, Hanukkah food and games are shared with a child guest, her wheelchair no obstacle to enjoying the menorah’s bright lights and holiday fun. Reading this story book aloud, for those who do celebrate Hanukkah, might just become a new family tradition!

As the days grow shorter and the countdown to a new president looms ever larger, I needily relish these glimpses of holidays to come, of times when virulent disease will not keep cautious, concerned families apart on such festive occasions. These books are indeed happy reading.

Being and seeing Black boys and men . . . . Transfixed this past month by the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, taking place just eight miles from my Bloomington, Minnesota home, I wondered what I could bring today to this shamefully epic conversation. When Daunte Wright was then killed just twenty miles from here, adding his name to the annals of police violence, I was horrified and questioned myself again. Nothing original has come to my White, middle-class mind, but I can shine a spotlight on a luminous, insightful picture book created by author “Tony Medina & 13 Artists” of color.

Being and seeing Black boys and men . . . . Transfixed this past month by the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, taking place just eight miles from my Bloomington, Minnesota home, I wondered what I could bring today to this shamefully epic conversation. When Daunte Wright was then killed just twenty miles from here, adding his name to the annals of police violence, I was horrified and questioned myself again. Nothing original has come to my White, middle-class mind, but I can shine a spotlight on a luminous, insightful picture book created by author “Tony Medina & 13 Artists” of color.  Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Boy (2018) was inspired—as

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Boy (2018) was inspired—as  Medina has joyfully, powerfully met the challenges posed by this form’s constraints, with no awkwardness in the cascading word pictures he paints. Each of the thirteen tankas—Medina’s “thirteen ways of looking”—is illustrated by a different artist of color. The book’s back matter satisfies our curiosity about these co-creators: Floyd Cooper, Cozbi A. Cabrera, Skip Hill, Tiffany McKnight, Robert Liu-Trujillo, Keith Mallett, Shawn K. Alexander, Kesha Bruce, Brianna McCarthy, R. Gregory Christie, Ekua Holmes, Javaka Steptoe, and Chandra Cox. Their visual art, each two-page spread inspired by a separate tanka, enhances our appreciation of this book, with its multiple. distinctive artistic visions.

Medina has joyfully, powerfully met the challenges posed by this form’s constraints, with no awkwardness in the cascading word pictures he paints. Each of the thirteen tankas—Medina’s “thirteen ways of looking”—is illustrated by a different artist of color. The book’s back matter satisfies our curiosity about these co-creators: Floyd Cooper, Cozbi A. Cabrera, Skip Hill, Tiffany McKnight, Robert Liu-Trujillo, Keith Mallett, Shawn K. Alexander, Kesha Bruce, Brianna McCarthy, R. Gregory Christie, Ekua Holmes, Javaka Steptoe, and Chandra Cox. Their visual art, each two-page spread inspired by a separate tanka, enhances our appreciation of this book, with its multiple. distinctive artistic visions.  Medina’s poems speak to human truths that transcend national borders and poetic forms. Similarly, the poems’ few references to “Anacostia,” the Black Washington, D.C. neighborhood that originally inspired this volume, are verbal touchstones rather than barriers to our understanding of their insights. Notably, while Medina acknowledges the impact of poverty and prejudice on Black boys, his emphasis is on their joy in life, their loving family and community support, and their many successes, now and extending into adulthood. As Medina writes in the book’s introductory poem, “Black boys shine bright in sunlight . . . We celebrate their preciousness and creativity/ We cherish their lives.” This positive, life-affirming book is a wonderful tonic to offset the limited, destructive views of Blacks publicized so recently in murderous police violence. In visual styles ranging from realism to abstraction, sometimes employing full color but in other instances using a dramatically limited color palette, the visual artists here enhance and elaborate upon Medina’s vision.

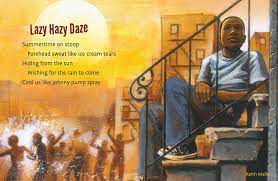

Medina’s poems speak to human truths that transcend national borders and poetic forms. Similarly, the poems’ few references to “Anacostia,” the Black Washington, D.C. neighborhood that originally inspired this volume, are verbal touchstones rather than barriers to our understanding of their insights. Notably, while Medina acknowledges the impact of poverty and prejudice on Black boys, his emphasis is on their joy in life, their loving family and community support, and their many successes, now and extending into adulthood. As Medina writes in the book’s introductory poem, “Black boys shine bright in sunlight . . . We celebrate their preciousness and creativity/ We cherish their lives.” This positive, life-affirming book is a wonderful tonic to offset the limited, destructive views of Blacks publicized so recently in murderous police violence. In visual styles ranging from realism to abstraction, sometimes employing full color but in other instances using a dramatically limited color palette, the visual artists here enhance and elaborate upon Medina’s vision.  It is hard for me to select favorites among these soul and eye-satisfying illustrated works. Perhaps the beaming toddler, embraced by his parents in “Anacostia Angel” or the pensive young man in “Lazy Hazy Daze.” Possibly the cartoon-like energy of the tweenagers depicted in “Athlete’s Broke Bus Blues” or “Givin’ Back to the Community.” Skip Hill’s vision for “Images of Kin” is also memorable. Its boy wearing a backward-turned baseball cap transformed into a crown, his face seemingly overlaid by—in Medina’s words—a “South East Benin mask/Face like a road map of kin” is so much more than the logo drawn on his T-shirt, “Southside Kings.”

It is hard for me to select favorites among these soul and eye-satisfying illustrated works. Perhaps the beaming toddler, embraced by his parents in “Anacostia Angel” or the pensive young man in “Lazy Hazy Daze.” Possibly the cartoon-like energy of the tweenagers depicted in “Athlete’s Broke Bus Blues” or “Givin’ Back to the Community.” Skip Hill’s vision for “Images of Kin” is also memorable. Its boy wearing a backward-turned baseball cap transformed into a crown, his face seemingly overlaid by—in Medina’s words—a “South East Benin mask/Face like a road map of kin” is so much more than the logo drawn on his T-shirt, “Southside Kings.” Yet I also cannot forget Robert Liu-Trujillos’s less upbeat spread illustrating “One Way Ticket,” whose words focus on small paychecks and mounting debts. Its subdued, limited colors show a serious-faced boy clutching a bag of groceries, with the words “One Way Ticket” drawn as a wall grafitto, an elevated train in the background. Also, “Cat at the Curb,” a tanka in which that animal has “nine lives not yet spent” [my emphasis], shows this animal darkly “Sandwiched between curb/And black radial tire.” These pages eerily bring to mind the videos of George Floyd’s car side murder. I cannot, it seems, long forget today’s raging questions about police violence.

Yet I also cannot forget Robert Liu-Trujillos’s less upbeat spread illustrating “One Way Ticket,” whose words focus on small paychecks and mounting debts. Its subdued, limited colors show a serious-faced boy clutching a bag of groceries, with the words “One Way Ticket” drawn as a wall grafitto, an elevated train in the background. Also, “Cat at the Curb,” a tanka in which that animal has “nine lives not yet spent” [my emphasis], shows this animal darkly “Sandwiched between curb/And black radial tire.” These pages eerily bring to mind the videos of George Floyd’s car side murder. I cannot, it seems, long forget today’s raging questions about police violence.  With that in mind, I will point you and tween age or teenage readers to a relevant graphic novel written earlier by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings, I am Alfonso Jones (2017). This award-winning work, centering on the fictional death of an innocent Black teen, also contains powerful examples of the real-life police murders that initiated the Black Lives Matter movement. I reviewed I am Alfonso Jones in depth

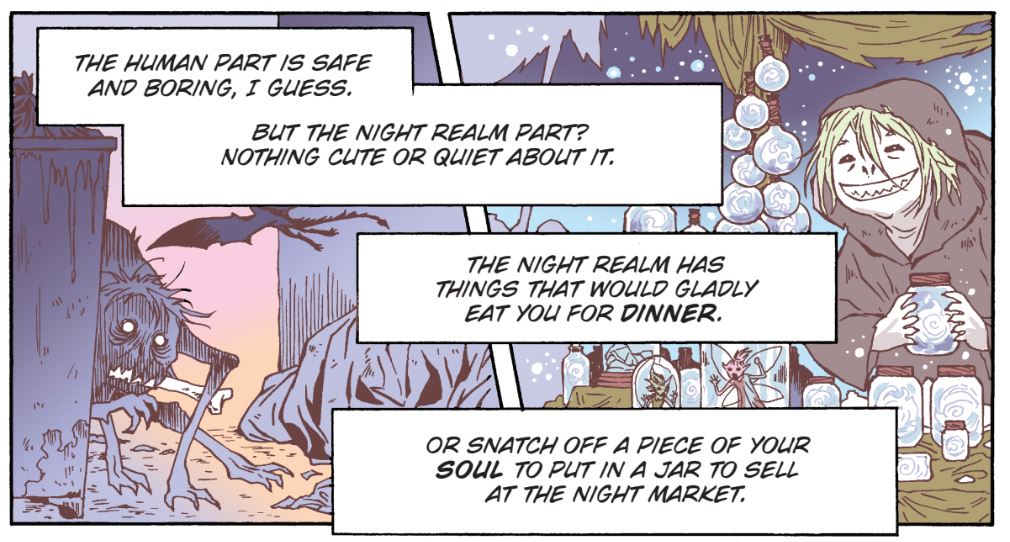

With that in mind, I will point you and tween age or teenage readers to a relevant graphic novel written earlier by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings, I am Alfonso Jones (2017). This award-winning work, centering on the fictional death of an innocent Black teen, also contains powerful examples of the real-life police murders that initiated the Black Lives Matter movement. I reviewed I am Alfonso Jones in depth  How excited are your students about schools beginning to open up for classroom lessons? If their delight is tinged by a bit of uncertainty, given this past pandemic year of interrupted attendance, a recent graphic novel may provide engaging reassurance. Its blend of fantasy with typical middle school events and issues offers a distanced focus on tween and teenage life—a storytelling step back from real-life school that matches how some kids now feel a bit new and strange in the classroom. Certainly, The Wiernbook’s Be Wary of the Silent Woods, Book 1 (2020) will please all readers with its fast-paced action, detailed cast of characters, and aptly colored images.

How excited are your students about schools beginning to open up for classroom lessons? If their delight is tinged by a bit of uncertainty, given this past pandemic year of interrupted attendance, a recent graphic novel may provide engaging reassurance. Its blend of fantasy with typical middle school events and issues offers a distanced focus on tween and teenage life—a storytelling step back from real-life school that matches how some kids now feel a bit new and strange in the classroom. Certainly, The Wiernbook’s Be Wary of the Silent Woods, Book 1 (2020) will please all readers with its fast-paced action, detailed cast of characters, and aptly colored images.  But it is Chmakova’s incorporation of another of her successes—the setting of her urban fantasy series Nightschool: The Weirn Books (2009 -2010)—into Be Wary of the Silent Woods that sets it apart from the Berrybrook Middle School books. In a recent interview, Chmakova revealed that she missed the fantastic world she had created in Weirn, with its older teen protagonists, and realized that nothing like it had been written for a middle-school audience. The author/illustrator says that Be Wary of the Silent Woods is an offshoot rather than a continuation of the earlier adventure series, with “a different place, different time, and an entirely different cast of characters, and also a different vibe . . . more lighthearted.”

But it is Chmakova’s incorporation of another of her successes—the setting of her urban fantasy series Nightschool: The Weirn Books (2009 -2010)—into Be Wary of the Silent Woods that sets it apart from the Berrybrook Middle School books. In a recent interview, Chmakova revealed that she missed the fantastic world she had created in Weirn, with its older teen protagonists, and realized that nothing like it had been written for a middle-school audience. The author/illustrator says that Be Wary of the Silent Woods is an offshoot rather than a continuation of the earlier adventure series, with “a different place, different time, and an entirely different cast of characters, and also a different vibe . . . more lighthearted.”

For most students, zoomed instruction has been a poor substitute for in-class learning. Yet COVID-19’s simultaneous lockdown on author/illustrator visits to schools and bookstores has given readers a wonderful opportunity: an abundance of zoomed interviews with these creative people. We can see and hear about how new graphic works were conceived and what their authors and illustrators especially want us to know about their work. For instance, a few weeks ago I had the opportunity to learn about a new novel that will especially appeal to tween/teen and older readers who enjoy scary fiction or are interested in African culture.

For most students, zoomed instruction has been a poor substitute for in-class learning. Yet COVID-19’s simultaneous lockdown on author/illustrator visits to schools and bookstores has given readers a wonderful opportunity: an abundance of zoomed interviews with these creative people. We can see and hear about how new graphic works were conceived and what their authors and illustrators especially want us to know about their work. For instance, a few weeks ago I had the opportunity to learn about a new novel that will especially appeal to tween/teen and older readers who enjoy scary fiction or are interested in African culture.  After the Rain (2021), written by John Jennings and illustrated by David Brame, is a wonderful adaptation of a short story by award-winning Nigerian-American author Nnedi Okorafor. Its brilliant colors, detailed pages, and strong storyline capture Okorafor’s acute observations about Nigerian and Nigerian-American culture. I was interested to learn—in that zoomed interview with Jennings and Brame–that Okorafor herself, a long-time friend of Jennings, was involved in this book’s creation. She provided the typical Nigerian cloth pattern featured on both its front cover and interior jacket pages as well as providing feedback on Jenning’s dialogue. It was also interesting to hear Brame discuss how Jennings’ remarks influenced some of his illustration choices. Multifaceted Jennings, himself a skilled

After the Rain (2021), written by John Jennings and illustrated by David Brame, is a wonderful adaptation of a short story by award-winning Nigerian-American author Nnedi Okorafor. Its brilliant colors, detailed pages, and strong storyline capture Okorafor’s acute observations about Nigerian and Nigerian-American culture. I was interested to learn—in that zoomed interview with Jennings and Brame–that Okorafor herself, a long-time friend of Jennings, was involved in this book’s creation. She provided the typical Nigerian cloth pattern featured on both its front cover and interior jacket pages as well as providing feedback on Jenning’s dialogue. It was also interesting to hear Brame discuss how Jennings’ remarks influenced some of his illustration choices. Multifaceted Jennings, himself a skilled

history book for readers 12 on up about the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma race massacre. Across the Tracks: Remembering Greenwood, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre will be published in May, 2021.

history book for readers 12 on up about the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma race massacre. Across the Tracks: Remembering Greenwood, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre will be published in May, 2021.  What a class act the new Biden-Harris administration is! President Biden and his team have brought purpose and hope these past weeks–including efforts that suggest how a return to U.S. classrooms will someday be safe for all. With that hope, today seems a good time to catch up with a great, eagerly awaited middle-grade novel centered on school life. Aptly, author/illustrator Jerry Craft has titled this companion volume to his

What a class act the new Biden-Harris administration is! President Biden and his team have brought purpose and hope these past weeks–including efforts that suggest how a return to U.S. classrooms will someday be safe for all. With that hope, today seems a good time to catch up with a great, eagerly awaited middle-grade novel centered on school life. Aptly, author/illustrator Jerry Craft has titled this companion volume to his  of Black 12 year-old Jordan, to appreciate Class Act. Yet having that familiarity will enhance enjoyment of this new volume, which follows Jordan into eighth grade at the prestigious, mostly-white private school, Riverdale Academy, that he attends just outside New York City. Class Act looks at and contrasts the experiences of comparatively light-skinned Jordan with those of his friends, darker-skinned Drew and Caucasian Liam. By deploying three central characters, Craft nimbly shows not only how skin tone affects racial interactions and prejudices but how economic class is a factor in personal and institutional expectations.

of Black 12 year-old Jordan, to appreciate Class Act. Yet having that familiarity will enhance enjoyment of this new volume, which follows Jordan into eighth grade at the prestigious, mostly-white private school, Riverdale Academy, that he attends just outside New York City. Class Act looks at and contrasts the experiences of comparatively light-skinned Jordan with those of his friends, darker-skinned Drew and Caucasian Liam. By deploying three central characters, Craft nimbly shows not only how skin tone affects racial interactions and prejudices but how economic class is a factor in personal and institutional expectations. Craft is never didactic, using insight and humor to communicate all these events–particularly the situations

Craft is never didactic, using insight and humor to communicate all these events–particularly the situations  Craft also uses humorous visual elements to reinforce his plot and themes. Confident, bossy seniors loom as literal giants over the sophomore students, while reluctant, sleepy students beginning the first day of school after summer vacation and other breaks—called “zombies” by Craft’s main characters–are literally depicted as zombies, with staring eyes, vacant expressions, and jerky body language. Class Act continues its creator’s enjoyable tradition of using punning titles for each chapter. While New Kid plays upon movie and TV show names, this companion volume plays upon kid lit book titles. Jerry Craft even lampoons himself, with one chapter’s double pun, titled “Mew Kid” and supposedly written and illustrated by “Furry Craft.” Of course, a cat is the main illustration there.

Craft also uses humorous visual elements to reinforce his plot and themes. Confident, bossy seniors loom as literal giants over the sophomore students, while reluctant, sleepy students beginning the first day of school after summer vacation and other breaks—called “zombies” by Craft’s main characters–are literally depicted as zombies, with staring eyes, vacant expressions, and jerky body language. Class Act continues its creator’s enjoyable tradition of using punning titles for each chapter. While New Kid plays upon movie and TV show names, this companion volume plays upon kid lit book titles. Jerry Craft even lampoons himself, with one chapter’s double pun, titled “Mew Kid” and supposedly written and illustrated by “Furry Craft.” Of course, a cat is the main illustration there.  This primarily full-color book also continues New School’s insertion of short, black-and-white comics supposedly drawn by artistic Jordan. This character’s words and pictures in the comics sarcastically point out the racism he feels and sees at tony Riverdale Academy. A visit from the Academy’s new sister school—a public school from an all-Black neighborhood–provides several chapters of further differences and misunderstandings between private Riverdale and the poorly-funded public school. In our real life COVID times, such differences frequently determine how and when it is safe for students to return to classrooms rather than learning online. Fictional Riverdale has ample space and, I suspect, state of the art air circulation systems, unlike its Bronx sister school, which even lacks books for many classes. Riverdale would probably be among those private schools which this past year only briefly shut down classroom instruction. Class Act‘s other visual storytelling elements include the effective use of rare, dramatically noticeable double page spreads (including chapter headings) and some pages in which the omission or changed size of panels appropriately heightens reader attention.

This primarily full-color book also continues New School’s insertion of short, black-and-white comics supposedly drawn by artistic Jordan. This character’s words and pictures in the comics sarcastically point out the racism he feels and sees at tony Riverdale Academy. A visit from the Academy’s new sister school—a public school from an all-Black neighborhood–provides several chapters of further differences and misunderstandings between private Riverdale and the poorly-funded public school. In our real life COVID times, such differences frequently determine how and when it is safe for students to return to classrooms rather than learning online. Fictional Riverdale has ample space and, I suspect, state of the art air circulation systems, unlike its Bronx sister school, which even lacks books for many classes. Riverdale would probably be among those private schools which this past year only briefly shut down classroom instruction. Class Act‘s other visual storytelling elements include the effective use of rare, dramatically noticeable double page spreads (including chapter headings) and some pages in which the omission or changed size of panels appropriately heightens reader attention. This past week’s winter solstice, overlapping with the rarely seen conjunction of planets Jupiter and Saturn, had me rethinking and rereading a similarly special, mysteriously meaningful new picture book, The Wanderer (2020). As I mused about how we rejoice each year, anticipating the brighter days that reliably follow our darkest night, I wondered about what other predictable rarities, such as that planetary conjunction, might remain beyond our sight. What might we do to explore and find such “unknowns”? With The Wanderer, Dutch author/illustrator Peter Van Den Ende stirs such questions, providing answers that provocatively yoke real-life situations to imaginary ones.

This past week’s winter solstice, overlapping with the rarely seen conjunction of planets Jupiter and Saturn, had me rethinking and rereading a similarly special, mysteriously meaningful new picture book, The Wanderer (2020). As I mused about how we rejoice each year, anticipating the brighter days that reliably follow our darkest night, I wondered about what other predictable rarities, such as that planetary conjunction, might remain beyond our sight. What might we do to explore and find such “unknowns”? With The Wanderer, Dutch author/illustrator Peter Van Den Ende stirs such questions, providing answers that provocatively yoke real-life situations to imaginary ones.  Readers young and old will enjoy poring over his pen and ink, cross-hatched drawings. These black and white images detail the adventures of a paper boat as it journeys across seas surrounding continents shaped like ours yet populated by strange creatures unlike any in our known world. Fish with human hands and horses, tigers, and elephants with fins are just some of the chimeras Van Den Ende depicts. Lavishly detailed in frequent full or double-page spreads, sometimes employing Escher-like patterns, his visual story shows some of these creatures helping the storm-tossed boat while others threaten it. One huge fish even ominously stands on a stack of shipwrecked vessels! Midway through the book, one of these hybrid, human-shaped creatures, along with a cat, boards the boat, joining it on its adventures.

Readers young and old will enjoy poring over his pen and ink, cross-hatched drawings. These black and white images detail the adventures of a paper boat as it journeys across seas surrounding continents shaped like ours yet populated by strange creatures unlike any in our known world. Fish with human hands and horses, tigers, and elephants with fins are just some of the chimeras Van Den Ende depicts. Lavishly detailed in frequent full or double-page spreads, sometimes employing Escher-like patterns, his visual story shows some of these creatures helping the storm-tossed boat while others threaten it. One huge fish even ominously stands on a stack of shipwrecked vessels! Midway through the book, one of these hybrid, human-shaped creatures, along with a cat, boards the boat, joining it on its adventures.  Do your spirits need a lift? In this time of raging COVID-19 and President Trump’s outrageous behavior towards President-elect Biden, my heart has been gladdened by picture books casting new light upon Hanukkah. One of these charming works is particularly well-suited for young readers whose families may celebrate Christmas as well as this upcoming Jewish holiday. All these books emphasize human determination, generosity, and emotional connections, regardless of religious affiliation—or lack of any affiliation. Their refreshing takes on Hanukkah, each deploying a child-friendly literary tradition in a new way, are comfortingly familiar even as they are engagingly different.

Do your spirits need a lift? In this time of raging COVID-19 and President Trump’s outrageous behavior towards President-elect Biden, my heart has been gladdened by picture books casting new light upon Hanukkah. One of these charming works is particularly well-suited for young readers whose families may celebrate Christmas as well as this upcoming Jewish holiday. All these books emphasize human determination, generosity, and emotional connections, regardless of religious affiliation—or lack of any affiliation. Their refreshing takes on Hanukkah, each deploying a child-friendly literary tradition in a new way, are comfortingly familiar even as they are engagingly different. The Hanukkah Magic of Nate Gadol (2020), written by

The Hanukkah Magic of Nate Gadol (2020), written by  In this book, Nate Gadol is a magical character credited not only with the holiday’s original supposed miracle but also with dispensing gifts to good needy Jewish people. Levine’s main story shows how the children of one 19th century immigrant family, the Jewish Glasers, receive winter holiday presents just like their Christmas-celebrating neighbors. In his final “Author’s Note,” Levine, who is Jewish, does not view the children’s wish for presents as a

In this book, Nate Gadol is a magical character credited not only with the holiday’s original supposed miracle but also with dispensing gifts to good needy Jewish people. Levine’s main story shows how the children of one 19th century immigrant family, the Jewish Glasers, receive winter holiday presents just like their Christmas-celebrating neighbors. In his final “Author’s Note,” Levine, who is Jewish, does not view the children’s wish for presents as a

Similarly, some familiarity with Hanukkah will enhance enjoyment of Little Red Ruthie: A Hanukkah Tale (2017), written by Gloria Koster and illustrated by Sue Eastland. This variation on “Little Red Riding Hood” proudly acknowledges its literary heritage in Koster’s opening dedication to her mother, “who gave [her] the gift of fairy tales once upon a time.” In an interview, the author has explained that another of her favorite fairy tales, the “Snow Queen,” inspired the icy, snow-laden setting of “Little Red Ruthie.” Her modern-day Ruthie is going to her Bubbe’s house (“Bubbe” is the Yiddish word for Grandmother) to again make potato pancakes, a traditional Hanukkah food, with her. In fact, Ruthie’s recipe for these “yummy ‘latkes’ ” (Yiddish for pancake) concludes this playful, positive book.

Similarly, some familiarity with Hanukkah will enhance enjoyment of Little Red Ruthie: A Hanukkah Tale (2017), written by Gloria Koster and illustrated by Sue Eastland. This variation on “Little Red Riding Hood” proudly acknowledges its literary heritage in Koster’s opening dedication to her mother, “who gave [her] the gift of fairy tales once upon a time.” In an interview, the author has explained that another of her favorite fairy tales, the “Snow Queen,” inspired the icy, snow-laden setting of “Little Red Ruthie.” Her modern-day Ruthie is going to her Bubbe’s house (“Bubbe” is the Yiddish word for Grandmother) to again make potato pancakes, a traditional Hanukkah food, with her. In fact, Ruthie’s recipe for these “yummy ‘latkes’ ” (Yiddish for pancake) concludes this playful, positive book. Unlike some traditional Red Riding Hoods, Ruthie does not require rescue by someone else. She reminds herself to be “brave as the Macabees,” the heroic warriors in the Hanukkah story, and she cleverly delays the wolf by playing upon his greedy appetite. Being an “excellent reader” also helps Ruthie, as reading Bubbe’s note helpfully explains where her grandmother is and when she will return. Determination, family feeling, and literacy—as well as the ability to prepare a delicious Hanukkah food, all the while explaining the holiday’s story—are the values and achievements extolled in this seemingly simple tale.

Unlike some traditional Red Riding Hoods, Ruthie does not require rescue by someone else. She reminds herself to be “brave as the Macabees,” the heroic warriors in the Hanukkah story, and she cleverly delays the wolf by playing upon his greedy appetite. Being an “excellent reader” also helps Ruthie, as reading Bubbe’s note helpfully explains where her grandmother is and when she will return. Determination, family feeling, and literacy—as well as the ability to prepare a delicious Hanukkah food, all the while explaining the holiday’s story—are the values and achievements extolled in this seemingly simple tale.  Family warmth and connectedness are also extolled in There Was a Young Rabbi: A Hanukkah Tale (2020), written by Suzanne Wolfe and illustrated by Jeffrey Ebbeler. This picture book draws upon the cumulative rhyme tradition exemplified in “There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly” and, particularly at this time of year, in the traditional English Christmas carol

Family warmth and connectedness are also extolled in There Was a Young Rabbi: A Hanukkah Tale (2020), written by Suzanne Wolfe and illustrated by Jeffrey Ebbeler. This picture book draws upon the cumulative rhyme tradition exemplified in “There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly” and, particularly at this time of year, in the traditional English Christmas carol  pages and on a few double-page spreads, we see images that add visual pleasure to such refrains as “There was a young rabbi who played dreidel to win. She watched it closely as it started to spin. /The dreidel—it spun. The rabbi—she won! Kosher brisket she made. At least ten pounds it weighed.” For young readers unfamiliar with Hanukkah, some pages have a brief boxed fact in unobtrusive type at the bottom of the page. Also, these readers will benefit from the short overview of the holiday provided on the book’s final page. (Youngsters will have to learn elsewhere that some Jewish denominations still do not accept women as rabbis.)

pages and on a few double-page spreads, we see images that add visual pleasure to such refrains as “There was a young rabbi who played dreidel to win. She watched it closely as it started to spin. /The dreidel—it spun. The rabbi—she won! Kosher brisket she made. At least ten pounds it weighed.” For young readers unfamiliar with Hanukkah, some pages have a brief boxed fact in unobtrusive type at the bottom of the page. Also, these readers will benefit from the short overview of the holiday provided on the book’s final page. (Youngsters will have to learn elsewhere that some Jewish denominations still do not accept women as rabbis.) Every reader will smile at Ebbeler’s cheerfully colorful, cartoon-like drawings, with grandparents whose features and big eyeglasses resemble the rabbi’s coming to celebrate one holiday night. On another night, Hanukkah food and games are shared with a child guest, her wheelchair no obstacle to enjoying the menorah’s bright lights and holiday fun. Reading this story book aloud, for those who do celebrate Hanukkah, might just become a new family tradition!

Every reader will smile at Ebbeler’s cheerfully colorful, cartoon-like drawings, with grandparents whose features and big eyeglasses resemble the rabbi’s coming to celebrate one holiday night. On another night, Hanukkah food and games are shared with a child guest, her wheelchair no obstacle to enjoying the menorah’s bright lights and holiday fun. Reading this story book aloud, for those who do celebrate Hanukkah, might just become a new family tradition!